The source code for this tutorial series can be found in this GitHub repository. The following list shows all articles of this series published so far:

<li>

<a href="/en/blog/2023/network-tutorial-1-overview/">Networking tutorial 1: General information and overview</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/en/blog/2023/network-tutorial-2-walking-skeleton/">Networking tutorial 2: The "walking skeleton"</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/en/blog/2023/network-tutorial-3-login-1/">Networking tutorial 3: Login 1 - The game client</a>

</li>

<li>

Networking tutorial 4: Login 2 - gateway and authentication server

</li>

<li>

<a href="/en/blog/2023/network-tutorial-5-login-3/">Networking tutorial 5: Login 3 - world server</a>

</li>

<li>

<a href="/en/blog/2023/network-tutorial-6-dtls/">Networking tutorial 6: Encrypted connections using DTLS</a>

</li>

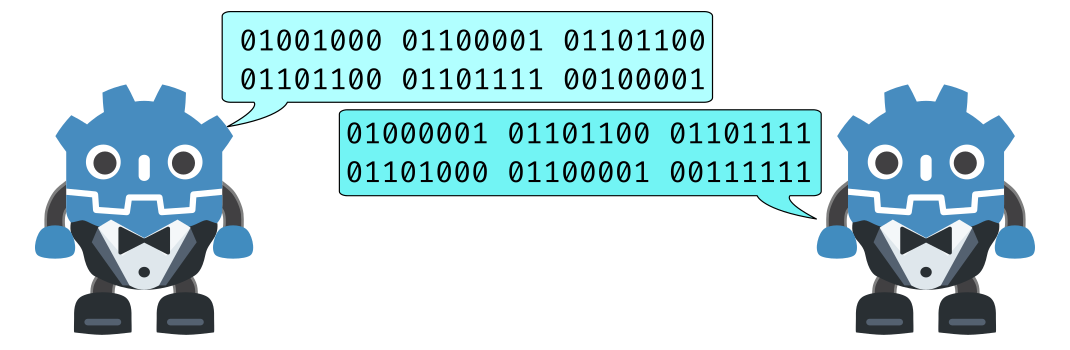

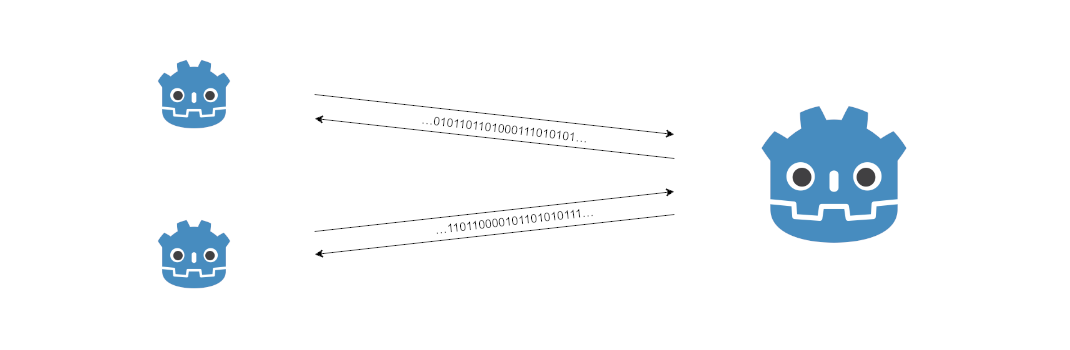

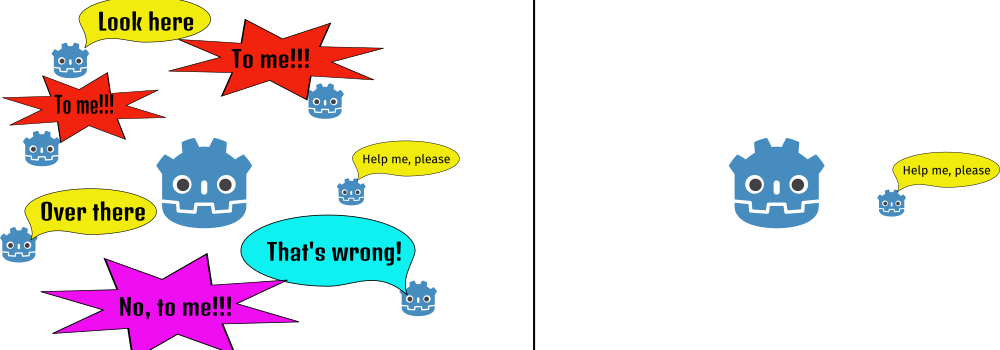

In the last article we created the game client to the point where it wants to contact the gateway server with login data. In this article, we will continue at this exact point and take care of the gateway server and authentication server. However, before we can take care of the actual login process, we first have to make the gateway and authentication servers familiar with each other and make sure that they trust each other. We use a mechanism that allows mutual authentication already during the connection setup and that was only introduced in Godot 4 in November 2022.

Midjourney

Midjourney