As already announced at the end of the last article, in this article I would like to show you some ways of trying to get Windows software to run under Linux. Unfortunately, I have to phrase it this way, as not all Windows software runs on Linux. The reasons for this vary greatly, but at least I feel that things have improved in recent years. Even if software manufacturers do not specifically create their own Linux versions, I have seen on occasion that they are at least making an effort to ensure compatibility with Wine.

In addition to highlighting the general possibilities for running Windows software on Linux, I would also like to demonstrate this using practical examples from Marmoset Toolbag 5 and the Affinity Suite. However, in this article, I will limit myself to “normal” software, so anyone hoping for games will unfortunately have to wait a little longer.

Before we really get started, here is the usual overview of all the articles in this series published so far:

- Linux? What the penguin!?

- Basic installation of the Linux distribution

- Installation of native Linux software

- Installing Windows software on Linux

- Gaming on Linux

- Unreal Engine on Linux

A first overview

Wine 🍷

The desire to run Windows software on Linux is almost as old as Linux itself. The central project here is Wine 🍷. Wine stands for “WINE is not an emulator”, and the name says it all. Wine does not emulate Windows; instead, it acts more like an interpreter between Windows and Linux. Technically, this works in a simplified way by Wine providing the implementation of the Windows API to the Windows program to be executed. Calls to the Windows API are then converted into “Linux commands” and forwarded to Linux. Since this “interpreting” is usually very efficient, Windows software can in many cases be executed without any noticeable difference in speed compared to “real” Windows.

In general, Wine attempts to provide the Windows API from Windows 3.1 to Windows 11. The older the Windows API, the more completely it is usually implemented by Wine. But since applications never use the complete Windows API, it is often possible to use current programs to their full extent even with the incomplete implementation.

Forks

Since Wine is an open source project, anyone can make changes as long as they comply with the license terms. That’s why you’ll encounter forks in various places from time to time. Let’s take a quick look at the two best-known ones that are still actively being developed.

CrossOver

In this context, we should also mention CrossOver. This is a commercial version of Wine from CodeWeavers. If you are willing to spend the money on CrossOver, you are entitled to support and a certain guarantee that specific software will run. Of course, changes to the Wine source code itself (through the LGPL) is contributed back to the Wine project, and CodeWeavers also employs some of the Wine developers directly, so by purchasing CrossOver, you are also supporting the Wine project to some extent. The big difference between using CrossOver and “pure” Wine is that CrossOver offers a graphical user interface and you don’t have to do everything via the command line. Also, if my memory serves me correctly, there are ready-made installers for some software.

Proton

I would like to briefly mention Proton here, as it is much more than a fork of Wine and is sure to come up again in our article on gaming under Linux. Proton is a Wine-based compatibility layer with a focus on gaming. Behind Proton is none other than Valve, although they also pay some CodeWeavers developers for development. At first glance, the biggest difference between Proton and “pure” Wine is that Proton has DXVK directly integrated. Put simply, DXVK is Wine in the graphics API environment and “translates” Direct3D commands into Vulkan commands.

Frontends

Wine offers a wide range of configuration options, but also requires setting environment variables, executing from the appropriate directories, and a few other things to keep in mind when using it directly from the command line. Fortunately, there are various front ends that attempt to simplify this issue and, ideally, make it possible for even novices to use. As is often the case, I will only discuss a small selection of the available options here. My selection is generally based on popularity and personal preference.

Lutris

Lutris is one such front end. Although its focus is primarily on games, other software can also be installed and configured using it. Lutris is not limited to Wine; for example, ScummVM games can also be configured using it. In addition, various accounts (GOG, Steam, etc.) can be stored, providing direct access to the respective game library.

In addition to the software itself, Lutris also offers the installer database. There you will find a large number of ready-made installer scripts that can be easily used in Lutris. This way, Lutris knows exactly which steps to take to get the desired application up and running. The scripts are created by community members and enable even less tech-savvy people to install the respective software. The scripts are based on YAML and the format is also documented.

Bottles

Bottles is another front end for Wine. In general, it seems much more minimalistic to me than Lutris, which is also due to the fact that it specializes in Wine. The name comes from the fact that Bottles creates “bottles” in which individual configurations and dependencies for different applications can be managed. Technically, this involves different Wine prefixes, a well-known technique that is also used by Lutris, of course. There are also some pre-built setups for applications, but the selection is still significantly smaller than with Lutris. I would say that Bottles is particularly suitable for users who want to use Wine without having to deal with complex manual settings.

WinBoat

WinBoat is still relatively new and therefore only available as a beta version so far. It is based on Dockur, which provides a very slimmed-down version of Windows 11 as a Docker container. Because Windows runs in a Docker container and the application image is accessed using RDP, the overhead is significantly lower than with a “normal” virtual machine and the image is much more pleasant and smoother than with VNC.

Unfortunately, there is currently no option for GPU passthrough, which means that applications launched via WinBoat are currently unable to access the GPU. As a result, some features may not be available, or performance may be worse than expected.

In practice

So, enough of the gray theory and background information. Let’s finally put what we’ve learned so far into practice.

Marmoset Toolbag 5

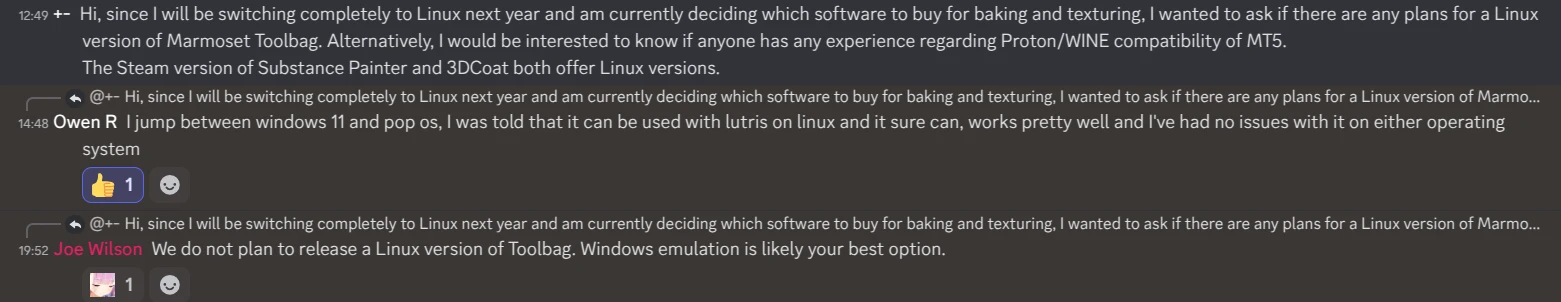

Before I bought Marmoset Toolbag 5, I already knew that I would be switching to Linux. So before purchasing it, I asked on the official Discord server about its Linux compatibility:

Discord screenshot confirming that Marmoset Toolbag 5 should run with Lutris / Wine.

That statement was enough for me, and I was therefore hopeful when I purchased the software. However, when I wanted to install Toolbag 5 while writing this article, reality unfortunately caught up with me.

During my attempts with Lutris, Marmoset Toolbag started up reliably at the end of the installation and I was able to log in without any problems, but as soon as I tried to click on something in the menu bar, it shut down immediately. Since this always happened during installation and the installer terminated with return code 512, Lutris assumed that the installation had been aborted due to an error. Therefore, I couldn’t continue experimenting with this version for the time being.

But Lutris isn’t the only option, as I described earlier, so I thought I’d give Bottles a try. No sooner said than done. The result was completely different, because Marmoset Toolbag 5 immediately displayed an error message upon startup, stating that it was unable to initialize the graphics system. But since the error message indicated that the installation had been successful overall, I was able to try out the various settings options in Bottles. Not that it did any good, because no matter what I configured, I haven’t been able to get rid of the message yet.

Since inquiring on Marmoset Discord didn’t yield any new insights and instead only reiterated that there are currently no plans to officially support Linux, and since I wanted to finish writing this article at some point, I decided to give up for now. I hope that with a little distance and calm, I will be able to get Marmoset Toolbag 5 up and running, as it is otherwise an extremely good piece of software and I would really like to explore its texturing capabilities in more depth.

I haven’t tried it with WinBoat yet. The installation should probably be possible without any problems, but since WinBoat unfortunately does not yet support GPU passthrough, Marmoset Toolbag 5 would not be able to access my GPU, so there would be no benefit.

Affinity Suite

There is now the Linux Affinity Installer, an unofficial project designed to make the Affinity suite as easy as possible to run on Linux. It supports both the “old” v2 version of Affinity and the “new” affinity by Canva. This project is not error-free either, so unfortunately it is not yet possible to save program settings in the v2 version, but as you can see from the related issue, the fix is actually available and just needs to be rolled out with the next release.

An AppImage is provided as a download, which must be made executable in order to run it. This can be done either graphically via the file manager or, of course, in the terminal:

~> chmod u+x Downloads/Affinity-3.0.2-x86_64.AppImage

~> Downloads/Affinity-3.0.2-x86_64.AppImage

In File Manager, this is usually done by right-clicking -> Properties -> Permissions, and then it can be started by right-clicking -> Run in console.

After starting, the installer should be self-explanatory, but if not, you can find instructions here. Usually, it should be sufficient to click on One-Click Full Setup and then wait for everything to be installed.

Conclusion & Outlook

I actually thought I would be able to write this article relatively quickly. But then reality caught up with me once again. On the plus side, you should now be able to see that I really do try out the things I write about. I still think it’s a shame that I can’t get Marmoset Toolbag 5 to work at the moment, but I have some hope for the future. Fortunately, I was able to find a solution for Affinity after all. It took more effort than I expected, but at least it works.

After all the work and “productivity” so far, I’ll devote the next article to the more enjoyable side of things: gaming. One article probably won’t be enough, but let’s wait and see.