We now have a working Linux system thanks to the last article. The next logical step for me is to take a closer look at software installation. Since there are various options available, as is usual with Linux, this article will primarily focus on installing native Linux software. But of course, this is not just an analysis for its own sake; as before, we are taking a goal-oriented approach. In the first article, I wrote that, in addition to the browser and (Libre)Office, at least the following applications should work in the end: Steam, Heroic Games Launcher, Blender, Marmoset Toolbag 5, Affinity Suite, Godot, Unreal Engine 5, Substance 3D Designer, Substance 3D Painter, and various programming tools (Python, Rust, C#, C++, and Kotlin). So, it is also necessary to find out which software has its own Linux versions and how these can be installed “best”.

Before we really get started, here is the usual overview of all articles in this series published so far:

- Linux? What the penguin!?

- Basic installation of the Linux distribution

- Installation of native Linux software

- Installing Windows software on Linux

- Gaming on Linux

- Unreal Engine on Linux

Installation options

Before I get to the various installation options, I will first discuss the differences between Windows and Linux in this area.

In the Windows world, it has long been common practice to run dedicated installation programs for software, and many people still do so. In the past, the sources were floppy disks, CDs, or DVDs, but in recent decades, the internet has become the primary source. This means that the procedure was, and still is, to obtain an installation program from more or less trustworthy sources, which then usually requires administrator rights to run correctly. Even though the Microsoft Store (or Windows Store until October 2017) has been an integral part of Windows since Windows 8, I have never used it myself and don’t know anyone who does. With Chocolatey and similar projects, there has also been a package manager for the command line since 2011, but I suspect that these solutions have not caught on outside of developer circles.

I don’t find that surprising anymore. The Windows world often feels like “take it or leave it” to me. Every program usually comes with all the necessary libraries (excluding Windows libraries). Some larger manufacturers even have their own launchers to handle un-/installation, updates, and configuration, thereby attempting to establish their own (sub)ecosystem.

Under Linux, this is traditionally very different. Each distribution comes with a package manager, which, as the name suggests, is responsible for managing (un-/installation, and updating) the packages and is the primary source of supply. Package managers also allow you to configure package sources, whose contents are cached by the package manager. Originally, the package sources were mainly located on storage media (e.g., the distribution’s installation media), which were read to create the cache. Thanks to the cache, it was possible to see the available packages even without inserting the storage media. Even today, when package sources are mainly used via the network/Internet, the cache is still very useful, as it is still more efficient to query the optimized cache than to wait for responses from various servers.

In this context, when talking about Linux, I always refer explicitly to packages, which can contain a wide variety of things. Although software and libraries are probably the most common types of packages, in the case of themes, they can also be configurations and/or graphics. Of course, libraries are also software, but since libraries are required by other software, i.e., they represent dependencies, they should be considered individually. This allows multiple packages to share dependencies and thus save storage space, as the dependencies only need to be installed once. Linux therefore traditionally takes a very cooperative approach.

Unfortunately, the traditional approach of managing software via the package manager does not always have advantages. As I mentioned earlier, the actual approach under Linux is a cooperative one. Unfortunately, this approach only works as long as all packages with the same dependencies have agreed on a specific version of these dependencies or the common dependencies ensure a correspondingly long backward compatibility. Another problem can arise if you want to use the latest version of a software that is not yet available in the package sources of the selected distribution. And when it comes to commercial software, we will have to consider alternative distribution channels, as hardly any manufacturer is willing to provide suitable packages for all distributions. Another reason for not using the official package sources may be that you want to use a specific version of a software or perhaps even the same software in different versions in parallel.

Sometimes manufacturers, especially of commercial software, also offer installers for Linux. The last time I used CrossOver, in addition to distribution-specific .rpm and .deb packages, a generic installer was also offered, which could then be executed in the command line.

If software comes with all the necessary dependencies included, as is usually the case in the Windows world, the software is sometimes simply offered as an archive for download. This then only needs to be unpacked to the desired location and the software is ready to run. JetBrains uses this method for the Linux versions of its various IDEs.

One approach that attempts to make it even easier for users is the so-called AppImage. Here, the entire software is “packed” into a single executable file.

All of the options presented so far have one disadvantage in common. They do not support sandboxing. As a result, as long as the software is running, it can access everything that the executing user has access to. Although this is actually the standard case on all desktop operating systems, it means that users must trust the software.

For those who have higher security requirements, at least for certain software, there are also projects that support sandboxing, so that the software has less extensive rights. The two best-known projects/technologies in this area are:

- Flatpak

- Open source project originally initiated by a RedHat developer

- Focus on desktop applications

- Sandboxing via kernel namespaces (similar to containers)

- No background services required

- Supported by a large number of distributions

- Often faster than Snap versions due to less overhead

- No integrated automatic updates

- Installation of Flatpaks does not require admin rights

- More complex than creating packages as a developer

- Flathub offers 1000+ applications

- Snap

- Initiated by Canonical, the company behind Ubuntu

- Originally intended for IoT use, but can now also handle GUI applications

- Sandboxing via AppArmor

- Requires

snapdas a background service - Actually only used in the Ubuntu ecosystem

- Usually slower than the Flatpak versions

- Automatic updates

- Installation of Snaps requires admin rights

- Easier than creating Snaps (packages) as a developer

- Snap Store offers 100!? applications

Installation

So, enough of the gray theory and background information. Let’s finally put what we’ve learned so far into practice. I’ve tried to choose examples that allow us to consider the installation options we’ve discussed.

GPU drivers

One of the first things I checked after installing the base system was the status of the GPU drivers. The quickest way to do this is with the lspci program in the command line:

> lspci -k | grep VGA -A3

0000:00:02.0 VGA compatible controller: Intel Corporation Alder Lake-HX GT1 [UHD Graphics 770] (rev 0c)

DeviceName: Onboard - Video

Subsystem: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd. [MSI] Device 13cf

Kernel driver in use: i915

--

0000:01:00.0 VGA compatible controller: NVIDIA Corporation AD106M [GeForce RTX 4070 Max-Q / Mobile] (rev a1)

Subsystem: Micro-Star International Co., Ltd. [MSI] Device 13cf

Kernel driver in use: nvidia

Kernel modules: nouveau, nvidia_drm, nvidia

lspci generally lists all installed PCI devices. The -k option additionally lists the active kernel drivers. To avoid having to search through the entire hardware list ourselves, the command output is forwarded to the following command using |. In our case, this is the grep command, which searches outputs or files for specific patterns, in this case for the string VGA. The -A3 option causes grep to display the following 3 lines for each line found.

Fortunately, the output result shows that drivers are loaded for both the integrated Intel GPU and the dedicated NVIDIA GPU. This means that CachyOS not only recognized my hardware correctly, but also installed the appropriate drivers directly.

How does Linux know when to use which GPU? To answer this question, there is a relevant CachyOS wiki page. There you can learn that all preparations were made automatically by CachyOS and that when using the proprietary NVIDIA driver, as in my case, you can now determine that the dedicated GPU should be used by setting the appropriate environment variables. If that’s too much work for you, you can also simply use the prime-run program, which can take care of setting the environment variables.

The wiki page lists further options, which we will also look at in the case of Lutris and Steam.

We have only installed a limited number of things here, so there has been no point in considering the various installation options so far, but even if there had been, I would always choose the package manager route whenever possible at this hardware-related stage, as this usually ensures that the drivers or packages are also updated when the system is updated.

LibreOffice

In my experience, LibreOffice is an adequate alternative to Microsoft Office for most use cases. The website has subpages for installation via RPM or DEB package, AppImage, Flatpak, and Snap. In addition, virtually every distribution provides suitable packages via the package manager.

Since I am not a power user of office applications and therefore do not rely on special versions, I find installation via the package manager to be the easiest, as this also handles (security) updates via the normal system update. To make it less difficult for people who are less familiar with the command line, I am choosing the Octopi program this time. Octopi is installed by default with CachyOS and provides a graphical interface for package management. There are generally two versions of LibreOffice:

libreoffice-fresh: Latest stable versionlibreoffice-still: Extensively tested version

I have never had any problems with libreoffice-fresh, so I am installing it again this time. If US English is not the desired language, you should also install the desired language pack to match the main package of the desired LibreOffice version. In my case, I am also installing libreoffice-fresh-de.

Blender

Blender is also available through various channels, e.g., via the website as an archive or as a Snap, or via Steam. In addition, as is often the case with open source software, it is available via the package manager.

Since I often need to use specific versions of Blender for certain projects, I always use the archive download. The archive can be easily unzipped into a specific folder, allowing me to use different Blender versions in parallel.

Substance 3D Designer (Steam version)

Some people may be surprised to learn that Substance 3D Designer has a native Linux version. Like its availability on Steam and perpetual license, this is likely another remnant from the time before Adobe acquired Allegorithmic. This is also probably why this Linux-compatible version is only available on Steam, especially since Adobe Creative Cloud does not run on Linux to my knowledge.

If you have the Steam version of Substance 3D Designer, the installation works as you would expect from Steam. No further steps were necessary for me. Even explicit startup using prime-run was not necessary to access the dedicated NVIDIA GPU.

Substance 3D Painter (Steam version)

The same introduction applies to Substance 3D Painter as to Designer. The basic installation also works as usual with Steam.

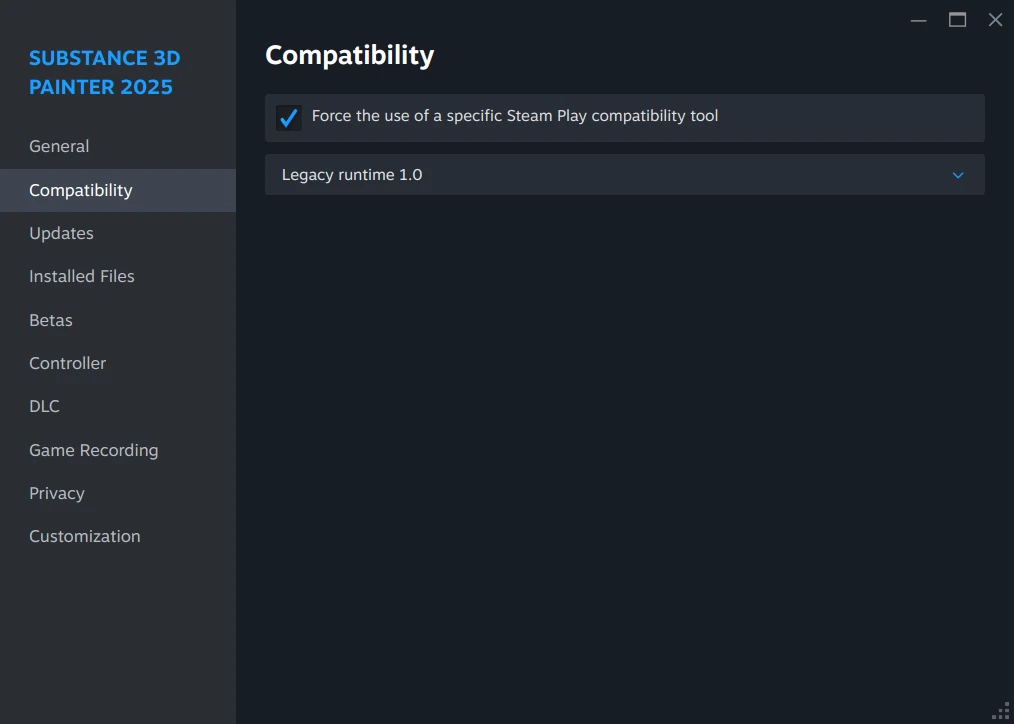

Unfortunately, there are currently a few compatibility issues that require some follow-up work. Fortunately, the developers are not only aware of this and intend to fix the issues soon, but have also documented appropriate workarounds. The first step is to set the compatibility for Substance 3D Painter to “Legacy Runtime 1.0” (see screenshot).

Set Steam compatibility mode to Legacy Runtime 1.0

In the second step, we need to install the xcb-util-cursor and libtiff5 packages. Painter should then start.

Unreal Engine

Unreal Engine for Linux is not installed via the launcher. In my opinion, this is both a blessing and a curse, as I find the launcher slow and poorly implemented, even though it bundles the installation, including Fab assets, in one place. In general, I should perhaps mention at this point that if you want/need to use UE 4, you have to compile the Linux version yourself. But since UE 4 is becoming less popular and I don’t currently have a project for it myself, I’ll spare us the descriptions here. However, if anyone needs it, instructions can be found in the accompanying documentation.

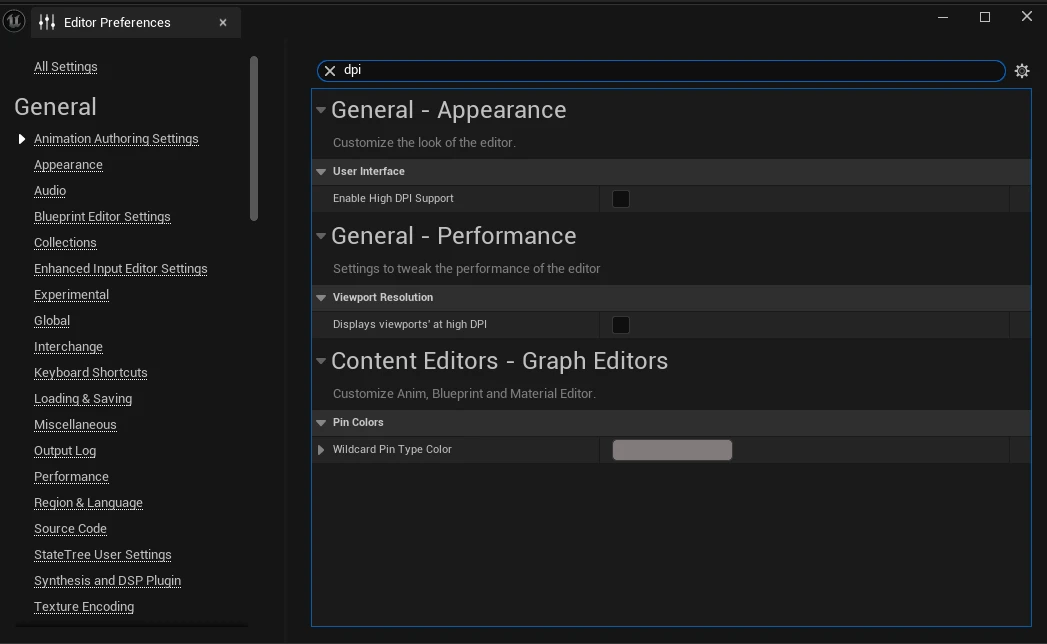

After unzipping the nearly 25 GB zip archive to the desired location, you can start UnrealEditor. The executable file UnrealEditor can be found under Engine/Binaries/Linux and then starts the project selection, as you are used to under Windows. If the tooltips or the interface in general appear too large, support for “High DPI” is enabled and should be disabled. You can also see the disabled editor settings in the screenshot.

Disable UE high DPI settings

This completes the basic installation. You can also find the Fab plugin on the download page. I haven’t had much experience with Unreal Engine on Linux yet, but that will probably change in the near future.

I do have one final tip, though: if you want to use the Houdini engine for UE on Linux, you should follow this guide. Since I don’t work with Houdini myself, as fascinating as I find the software, I couldn’t test it myself.

What next?

In the next article, I will focus on installing Windows software on Linux. Marmoset Toolbag 5 and Affinity Suite 2 will serve as examples. But don’t worry, the topic of gaming with Proton will also be covered, where Heroic Games Launcher, Lutris, and Steam will be examined in detail.